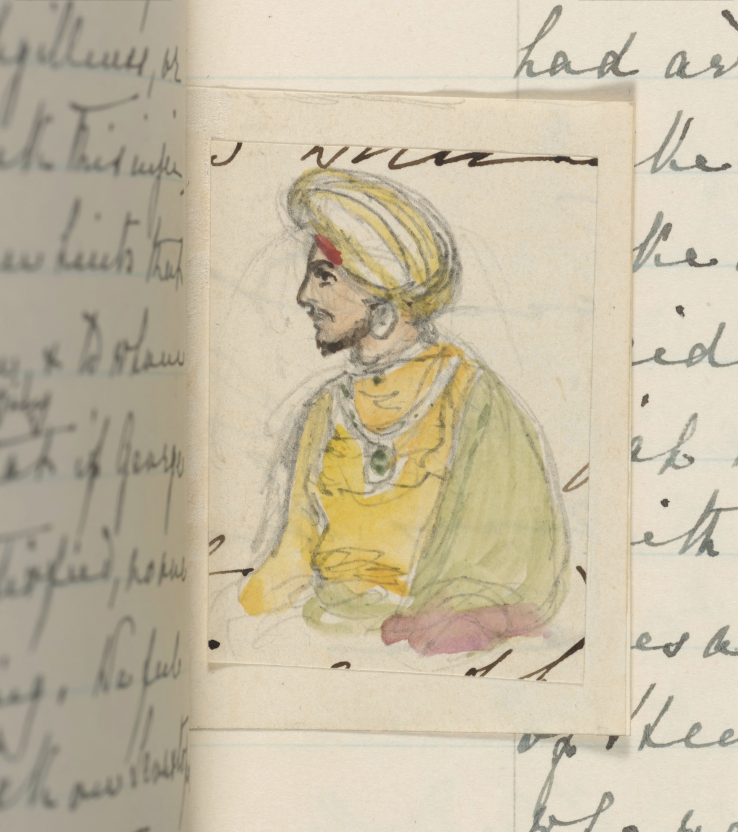

Queen Victoria and Maharaja Duleep Singh

The relationship between Queen Victoria and Maharaja Duleep Singh, the last ruler of the Sikh Empire, offers a revealing glimpse into the personal and political dynamics of British imperial rule in the mid-nineteenth century.

Exiled from Punjab as a child and brought to Britain under the guardianship of the East India Company, Duleep Singh came to embody the defeated Sikh Empire itself: at once a dispossessed sovereign, an imperial subject, and a royal ward. His position was shaped by both sympathy and control, a tension that is especially evident in Queen Victoria’s correspondence and journals.

Writing from Balmoral to Lord Dalhousie in October 1854, Queen Victoria expressed her concern for the Maharaja’s security:

“this young prince has the strongest claims upon our generosity and sympathy; deposed, for no fault of his, when a little boy of ten years old, he is as innocent as any private individual of the misdeeds which compelled us to depose him and take possession of his territories. He has besides since become a Christian, whereby he is for ever cut off from his own people.… There is something too painful in the idea of a young deposed Sovereign, once so powerful, receiving a pension, and having no security, that his children and descendants, and these moreover Christians, should have any home or position.”

Contemporary accounts reveal an unexpectedly intimate attention to the young maharaja’s health and education. The Queen closely followed his studies, welcomed his enthusiasm for activities such as skating, carpentry, fencing, dancing and museum visits, praising his curiosity and sociability.

In her journals, she repeatedly described him as cheerful, talkative and eager to learn, noting his interest in both British customs and conversations about his own country.

As an adult, Duleep Singh’s position grew more complicated: he remained a potent symbol of the lost Sikh Empire and continued to enjoy Queen Victoria’s personal regard.

Accounts from those close to him reveal a man who was, quite understandably, deeply disappointed by his treatment at the hands of the state.

Despite this, he retained an enduring, if increasingly strained, affection for the Queen herself.

To explore this story further, including contemporary accounts and visual material, see Eleanor Nesbitt’s ‘SIKH: Two Centuries of Western Women’s Art & Writing’, available to buy here.